We are nearing the end of our archaeological mystery tour, which began in Egypt with John Anthony West and continued to Ibiza’s ancient protector, the dwarf-god Bes via the Hall of Records, the Well of Laundry-Lists and a lost temple in Bahariya Oasis. The charismatic Egyptian deity may have given his name to Ibiza, but his cult faded gradually from sight during the early Christian era - which brings us to a forgotten novel by Robert Goldston, The Catafalque (1958). The Celtic (uncial) lettering of its cover reflects a truly bizarre archaeological plot:

High on a spray-swept promontory the ancient Castle of the Kings stands grim and forbidding above the fishing village of San Pedro del Rio in Catalonia. Deep within its vaults, an expedition led by a famous American archaeologist searches into the past for the tangible remnants of a strange Christian legend. A sinister web of intrigue, guilt and betrayal unfolds as each member of the expedition falls under the mysterious spell of the search and is led through his own past to some deeply buried terror.

[blurb]

Catalonia? The Gothic castle on the jacket was actually whisked across from Segovia by the publisher’s artist (it here towers over lateen-rigged boats and fishermen’s houses), but Bibliomaniacs’ Corner can now reveal for the first time that the real inspiration lay closer to home. Here’s what the American publisher (Rinehart & Co.) has to say about the author:

Robert C. Goldston, the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in April, 1957, for creative writing in fiction, has won acclaim with publication of his first novel The Eighth Day in 1955. Born in New York in 1927 and educated in Los Angeles, the Midwest and at Columbia University, Mr. Goldston has served in the U.S. Army, sailed a schooner on the Great Lakes and worked as a book designer for several publishing houses. He currently resides with his wife and two small daughters in the Balearic Islands.

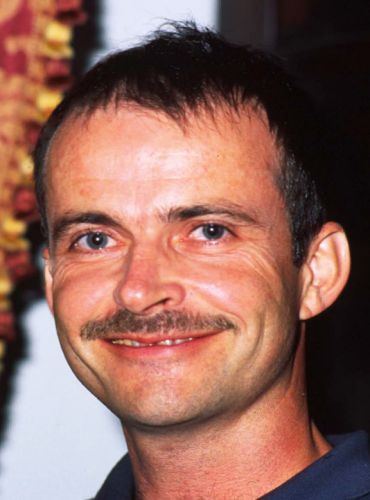

So we’re getting warmer. The Balearic Hemingway in the accompanying photo stares moodily right of stage, and indeed he did have rather an unusual archaeological quarry in his sights. The column against which he is leaning belongs to Ses Estaques, Norman Lewis’s recently-abandoned writer’s den just outside Santa Eulalia del Rio (see Ibiza History Culture Archive article Part Thirteen in Weekly Edition 075 of Saturday 3rd August 2002). A revealing location indeed for a photo-shoot: quite apart from the connection with Lewis and local archaeologist Carlos Román (who built it) ses Estaques lies at the foot of the Punta de s’Esglèsia Vella - ‘Headland of the Old Church’ - which according to local lore marks the spot from which the settlement’s original church fell into the sea just after the local population had emerged from mass one bright Sunday morning. This colourful legend perhaps set Goldston on the trail of how and when Christianity first arrived on Ibiza. Carthage and neighbouring Numidia, early strongholds of the faith, lay just across the sea while the Dead Sea scrolls (discovered between 1947 and 1956) were very much in the news. The hot historical subject in 1957 were the Essenes, a splinter sect which formed a missing link between Judaism and early Christianity. If one of Jesus’ brothers, James, did indeed sail to Spain shortly after the crucifixion, then what about the other more obscure (and reviled) sibling, Jude? This is the teasing riddle around which Goldston has built this unusual work of fiction.

Little more is know these days about early Christianity in the Pityuses than was the case in 1958, so the field was - and remains - wide open. In the opening chapter our sleepy fisherman’s village (a thinly-disguised Santa Eulalia) is jolted to life by the arrival of an academic caravan made up of Dr Wilfred Carrol (a respected archaeologist from Philadelphia), his redhead daughter Stephanie, two student assistants from Heidelberg (palaeographer Hans Kreuger and Polish architect Clopec), a butler who answers to the name of Mr Simpson and a sheep dog called Mithridates. The local team includes expatriate American archaeologist-turned-wino Frederick De Vries, a sympathetic and popular priest called Don Carlos, a bossy lesbian condesa, the Secretary of the local Falange (Don Miguel), Catalina the maid, Pedro the fisherman and ex-Republican Antonio Serra, who owns the general store and cheats a little on the side.

Carrol has been drawn to this remote backwater by De Vries’s discovery of an Essenic ring and the remote prospect of coming to the end of a ten-year treasure hunt, which began when he purchased an ancient scroll in Palestine. The plot thickens when Don Carlos mentions an old document among church papers describing the ceremonial burial of a man he assumes to be James the Apostle. At this point a slight detour for history buffs may be in order: legend has it that James was the first person to bring the Christian gospel to Spain around 40 AD and that the Virgin Mary appeared miraculously to him in Saragossa, leaving as material proof the sacred pillar which became the focal point of the nation’s metropolitan basilica. Although James was later beheaded by Herod Agrippa in Palestine, the corpse miraculously made it back to his adopted land thanks to a sail-less boat, was deposited near the Galician coast and discovered by a hermit eight hundred years later (813 AD), becoming a rallying symbol for the Reconquista and the object of Europe’s most important pilgrimage - Santiago de Compostela. Are you still there?

Goldston’s original ploy is to find a role for Judas Iscariot and ‘San Pedro’ (i.e. Santa Eulalia) in this celebrated legend. We will take a look at the historical Judas later on, but for now let us return to that fictitious Palestinian scroll which introduces Judas as the Messenger to the West (replacing St. James) and identifying his place of burial beneath the main turret of a castle. By the light of the full moon our intrepid American archaeologists set about looking for ‘the shadow of the needle’ mentioned in Don Carlos’s document. With a little help from the nose of trusty Mithridates they indeed find the burial vault of Judas. The catafalque itself has long been reduced to worm-eaten fragments, but there is a gold death mask as well as a sealed pottery jar - Carrol’s ‘holy grail’. In the following exegesis about the Essenes and the Early Church, half-Jewish Goldston presents Judas as a James-like figure who escaped the Roman dispersal of the sect at Qumran after the First Jewish Revolt (AD 68) and was ‘sent to a place in the West, bearing sacred documents’.

Having come to grips with all this background info on Proto-Christian splinter movements, the reader is naturally curious about the contents of the ‘Judas Scroll’, but Goldston will have none of that. Instead he devotes the second half of his novel to sub-plots and flashbacks involving expiation of Nazi or Fascist guilt. There is also a Spanish Civil War element, carrying on where Elliot Paul left off in The Life and Death of a Spanish Town (1937, subject of a future article): while diving off the headland, quisling Clopec chances across a watertight metal box which contains ten typewritten pages listing locals, many still alive, involved in an underground Republican organization. After offering it to the fascist condesa for $25,000, he has a sudden change of heart and flings it back into the sea, only to be shot dead by Antonio Serra, who is far more concerned about his daughter’s virginity. Then we have the arrival of a Jesuitical Don Luis from Madrid, ostensibly sent by the Bishop to inquire into the unorthodox practices of Don Carlos. Other deviations from the plot include a description of a concentration camp to which a shell-shocked Kreuger (ironically, a Jew) is sent as a guard, and Don Miguel’s project to build a road and tourist centre for busloads of culture vultures at Es Cuyeram.

Towards the end there is a sudden acceleration of pace: Don Luis reveals that he is also an official from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, empowered to take possession of the death mask and manuscript on behalf of the Spanish state. They will be forwarded to Madrid and eventually Rome being ‘of mild interest as records of heretical sects’ rather than earliest known version of the Christian gospels. Carrol has a nervous collapse during which De Vries’s affair with his wife and the reason for her death during an archaeological campaign in Persia come to light. Meanwhile, in the bowels of the Castle Don Carlos stumbles into a geographical time warp and is transported to the monastic fortress above the Dead Sea on the eve of its destruction by Roman legions. He eavesdrops on a conversation in which Judas is taken to task for his betrayal, but counters with information about the Roman attack and urges the other apostles to hide their precious documents in nearby caves. He also presses them to take the gospel further a field, to Alexandria and Rome where money and support will be forthcoming.

In the final scene manly De Vries assumes responsibility not only for Stephanie (still trembling after an ordeal with the lesbian countess in Tanit’s sanctuary) but for the entire expedition so as to prevent the Judas Scroll being consigned to dusty oblivion within the Vatican. The Countess takes her final leave of Don Carlos (on his way to a remote Asturian mining village - thanks to Don Luis’s report) with an impassioned tirade about female sexuality:

Woman does not exist in Spain, does she, Padre? You think that. You have taught that, all of you. But they do. I could mention names that would shock you. One finds love where one can. It is not so simple as you think. You think you can frighten me with goblins and threats. But you cannot. Do you know why? Because I am not a Catholic! I have not been a Catholic since I learned to love … Beautiful faces with full lips. Am I shocking you, Padre? Then listen more … I am very strong. Stronger than many men. Stephanie excited me in a particular way.

p. 299

Heady stuff for 1958. In fact the author was to pay a stiff price for his caricature of Franco on page 172: “… the fat fratricide sitting on a gilt throne in Madrid, staring past his stuffed Jefes into the black regions promised him by the half men bishops ... those puffed and fearful eyes that gazed paternally from the faces of newspapers and posters and postage stamps and coins.” He was expelled the following year and only allowed to return after the intervention of local resident Henri de Vilmorin (De Vries?) and Franco’s own brother. As the crestfallen expedition is departing for Barcelona, Simpson reveals that fifty photographs of the mask and scrolls are safely stowed in a box of sanitary napkins. The Spanish customs officers will hardly think to look there. The worldly and sophisticated Don Luis is appalled to find that he is to be the new priest of San Pedro, a fitting punishment for his duplicity and lack of Christian principles.

So much for the novel. What about Judas Iscariot? Who was the historical figure behind the Gospels and where might his body have been laid to rest? The linguistic and textual complexities of biblical scholarship have had to wrestle from the very beginning with deeply-entrenched religious dogmas, leaving historical truth at the very back of the academic agenda for centuries - if not millennia. Traditional scholarship pairs Judas with the Judean town of Kerioth (identified by one nineteenth-century scholar as Khirbet el-Quaryatein in the southeast Judean wilderness), making him an outsider from the start among the Galilean disciples. But recent investigators have been intrigued by a possible connection with the Zealots who spearheaded Roman Palestine’s freedom movement. A little-known version of Judas’s nickname in early manuscripts is ‘Skarioth’ or ‘Skariotes’, which appears to derive from sicarius (Latin for ‘dagger-man’), a contemporary Zealot nickname which evoked that of their predecessors, the Maccabeans (from the Hebrew maqáb, ‘hammer’). John and James had similar warlike epithets (boanerges meaning ‘Sons of Thunder’, Mark 3:17), while Simon was simply ‘the Zealot’ (zelotes, Luke 6:15). Not exactly what you’d have expected of the world’s prototype pacifist movement.

Jude was not only an exceedingly obscure disciple, but probably the unluckiest - victim, it would seem, of the Pauline Church. The political and literary agenda of any propaganda war requires villains as well as heroes and Antioch at the time of Paul – like Geneva at the time of Calvin - did not shrink from blackening reputations elsewhere to further its cause. The original apostles (some still in Jerusalem) were depicted as naïve followers with semi-political leanings, while the special role of Arch-traitor was reserved for Judas, then head of the ad hoc regency awaiting the Messiah’s return. Following the crucifixion, Jesus’ brother James had been in charge of the Jerusalem church, but what is often overlooked is that another brother, the apostle Judas (there was probably only one) was the third regent. Moreover, Judas’s very name bore a close resemblance to that of the Jewish kingdom at a time when the gentile church was distancing itself from those seen as responsible for the crucifixion.

Little is known about the later life of Judas, although he could well have been the author of the brief and elegantly-written epistle which bears his name. He is supposed to have preached the gospel in Judaea, Samaria, Syria and Mesopotamia before returning to Jerusalem in 62 AD to help with the selection of its bishop. His martyrdom in Sufian in Persia is described in an apocryphal work, The Passion of Simon and Jude, together with that of Simon the Zealot (they share the same feast day). Other legends claim he was killed by a saw or curved sword in Syria and Armenia, hence the fact that he is often depicted holding an axe or halberd. It seems more likely that after Hadrian’s destruction of the holy city in 70 AD, he presided over a scattered community of Jewish Christians in Aleppo and Damascus, known as the Ebionites after the Hebrew word for ‘poor’, ebyon. Because their observance of Jewish law was regarded as heretical, their writings were mostly suppressed by the Church. Little wonder that their leader Jude was defamed and well and truly buried by religion and history alike. Matthew (27:5) had him hang himself in shame, giving Cercis siliquastrum (a close relative of the carob) the name of Judas Tree, its white flowers blushing purplish-pink forever after in shame. Acts (1:18) bestowed on him a truly bizarre fate whereby he stumbled headlong and then self-exploded in the middle of a field bought with the thirty pieces of silver. Other, more reliable, gospels maintain a tight-lipped silence.

And the ‘Castle of the Kings’? There is a Balearic ‘Castell del Rei’ in Mallorca. It occupies a truly majestic site 1,500 feet above the waves just north of Pollensa, and its origins are indeed shrouded in mystery. It became a key stronghold from 1229 to 1231 when an Arab chieftain took refuge after James the Conqueror stormed Palma, again in 1287 when Alfonso III of Aragon took the island, and finally in 1343 when forces loyal to Mallorca’s last king James III held out against the Catalan ruler Peter II. The courtyard has a deep well. There is also, of course, Ibiza’s ancient Castle at the top of Dalt Vila. Archaeologists are digging there right now. Spanish ones.

Next time you’re enjoying the panoramic view from the summit of the Punta de s’Esglèsia Vella, spare a thought for the first evangelisers of the Pityuses. Perhaps James the Apostle - or even Judas himself - may have stopped off on his way to Spain. And in case you’ve ever wondered who or what exactly was behind the Beatles anthem, click on http://www.epinions.com/musc-review-6D50-B56CBA7-3A198BC2-prod4. Goldston beat the Fab Four to it, though, by ten years: Take a sad song, and make it better.

Martin Davies

martindavies@ibizahistoryculture.com