Emily Kaufman's profile of Martin Davies (written in 2002) can be found in the Renaissance Man article.

The Med's premier party island might not seem a particularly promising locale for bookworms or library rats as they say in Spain, but such cunning creatures know better than to judge things merely by their covers. A good number have been making their way south by ship, plane and even the odd bit of driftwood ever since the magic word 'Ibiza' began to be whispered in leaky garrets and among editors in the know. It was reported that budding Hemingways could flourish in these latitudes on nothing more than fresh air, sunshine and a daily bottle of coñac. The present series is merely a preliminary exploration of the field, which could be likened to a completely unknown planet in the immense universe of printed matter. Our initial reconnaissance will not only throw new light on one or two old favourites, but also introduce some obscure works, which perhaps deserve a wider audience. So without further ado, let us uncork a few of those dusty old bottles and see what's inside:

Fact 1: Ibiza and Formentera feature prominently in over one hundred and fifty novels and travel accounts in English, German, French, Dutch, Norwegian, Swedish and Finnish, matched by a comparable number in Spanish and Catalan. Albanian fails to make this list, but the author of a recent English travel book about the Balkan fastness has a retreat in a remote part of San Carlos.

Fact 2: Ibiza was once known in bohemian circles from Dundee to Dunedin as the Island of Painters; a far better moniker though would have been the Island of Writers (Would-be Writers).

Fact 3: A volume translated and introduced by your own correspondent entitled Writers and Painters in the Pityuses (in the original Dutch Literair Ibiza) will be appearing in local bookshops on the Day of the Book, 23rd April. Despite an excellent text and superb photographs, it represents the mere tip of the 'bookberg', only covering the Dutch and a handful of Americans between 1957 and 1963. When seen against the full riches of the Ibicencan literary banquet, it could be likened to a modest tray of delicious tapas.

Fact 4: Among top literati who came to Ibiza in search of inspiration and/or cheap liquor we find Albert Camus, Laurie Lee, Janet Frame, Norman Lewis, Walter Benjamin and Jan Cremer (the Dutch Rabelais). Shakespeare and Proust would certainly have put ashore had they known about it.

Fact 5: Shakespeare did know (details in later article).

Fact 6: A new and highly-acclaimed Spanish version of À la recherche du temps perdu is being nurtured into being in a quiet island backwater. The Madrid-born translator and his New Jersey wife possess one of the largest private libraries in the Balearics; an entire wall, from floor to ceiling, is given over just to dictionaries. The couple wear their bibliomania with honour and pride.

Fact 7: Laurie Lee's classic memoir about a Cotswolds childhood, Cider with Rosie (published in the United States as The Edge of Day) was partly written in a rented chalet in Santa Eulalia.

Fact 8: There are two eighteenth-century German opera librettos which take Formentera as their setting (details to follow).

Fact 9: The twentieth-century's greatest literary fake, The Autobiography of Howard Hughes, was written between 1969 and 1971 in a writer's studio overlooking Ibiza Town. Life magazine twice took the scandal as its cover-story, having earlier been duped into buying serialization rights. Exactly three decades later, it has just been published for the first time.

Facts 10-12: Some tall stories: there is a Swiss novel dating from 1957, whose title translates as 'Dreams End on the Border with Heaven'. It is about a local fisherman who climbs Es Vedrà. In 1936 a German novel was published under the title Die Nonne von Ibiza. The plot revolves around a Danish painter who falls in love with a nun in San Antonio's convent. Shortly after giving birth to a golden-haired girl, the latter leaps to her death from a nearby cliff. An American novel from 1958 has archaeologists unearthing the remains of Judas Iscariot on a hilltop castle just outside a thinly-disguised Santa Eulalia. One of its more risqué episodes is a lesbian seduction scene in the Carthaginian cave-sanctuary of Es Culleram, high on a wooded crest overlooking the inlet of San Vicente.

Fact 13: A likely tale, this one: in a French novel published in 1902, Don Quixote was placed in charge of Ibiza for five whole years.

Fact 14: Agatha Christie gave Ibiza a cameo in 4.50 from Paddington:

'But my brother Cedric is a painter and lives in Ibiza, one of the Balearic Islands.''Painters are so fond of islands, are they not?' said Miss Marple.

So, now I have your attention, shall we unroll the magic carpet?

Children's Books

Can there be anyone who doesn't have a soft spot for children's books? Not only do they have colourful pictures and heart-warming stories, but they also solve birthday-present crises and satisfy thespian yearnings when read aloud at bedsides; for language learners they are easily digestible, for native speakers a mouth-watering piece of cake. Last but not least, they seem too heavy neither in hands nor on pockets.

There are at least seven English-language children's books set on Ibiza and Formentera and all are far superior to anything in this genre produced in Spanish or Catalan. Eva-Lis Wuorio's The Island of Fish in the Trees, published in 1962 in Cleveland, Ohio is the first and probably the best. The illustrations are by Edward Ardizzone (1900-79), one of the leading names in twentieth-century book illustration. Seven exquisite double-page watercolours provide evidence of someone at the very top of his profession. So impressive and convincing is the illustrator's attention to detail that it seems quite possible Ardizzone made a special trip to Formentera; alternatively, he was sent sufficient photographs by the Finnish-Canadian writer to build up an excellent picture of local life and manners. The story follows Belinda and her little sister to the three corners of the Pitiusa minor in search of kind Señor el Médico on behalf of a doll with a particularly severe headache. One scene depicts the square of San Francisco (Javier), the old island bus bursting at the seams with human and animal life. Others transport us to tiny fishermen's coves in which are moored picturesque lateen-rigged feluccas. The ever-present juniper skeletons festooned with fish curing in the salt breeze, provided not only the title of the book (The Island of Fish in the Trees) but also the name of Formentera's principle port - Savina (a local variety of juniper). Belinda and her sister, the former clutching the long-suffering doll, wear elegant but old-fashioned clothes. There is not a backward baseball-cap in sight - in fact, no one seems to have heard of sunglasses.

Next week we shall take a look at two children's books from 1965 set on the Pitiusa mayor. Both, - Tal and the Magic Barruget and Pietro and the Mule - have clangers in their titles. Perhaps you can spot them? But before lights out, let us turn briefly to Walter Benjamin, the greatest bibliophile ever to have set foot on our shores (one of his essays is simply entitled 'Unpacking My Library' - his ex-wife had by that stage already taken possession of his highly-prized children's books). He spent his first summers of exile, 1932 and 1933, in and around San Antonio, writing the first draft of another classic childhood memoir, A Berlin Childhood Around 1900 (which will shortly be published for the first time in English). The following passage is taken from a radio talk on the subject of children's literature, delivered in 1929:

We do not read to increase our experiences; we read to increase ourselves. And this applies particularly to children who always read in this way. That is to say, in their reading they absorb; they do not empathize. Their reading is much more closely related to their growth and their sense of power than to their education and their knowledge of the world. This is why their reading is as great as any genius that is to be found in the books they read. And this is what is special about children's books.

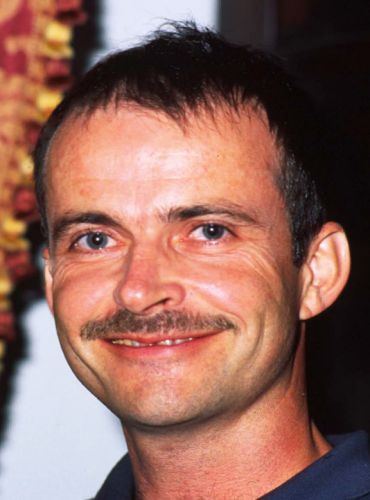

Martin Davies