'O Solon, Solon, you Greeks are always such children; there is no such a thing as an old Greek.'

Egyptian priest, reported in Plato’s Timaeus (ca. 360 BC)

Back in July I mentioned an etymological link between bibliomania and papyrus, and the time has finally come - as we will soon be sounding biblio-mysteries from ancient Egypt - to fill you in. ‘Papyrus’ is a word so ancient that scholars are far from agreed about its original meaning. One oft-cited theory links it to ancient Egypt’s royal bureaucracy - pa-pyrus meaning ‘that which belongs to the House (pa)’; plausible, I thought, until Dr Ossama Alsaadawi drew my attention to the fact that bab, the precious rolls on which ancient Egyptians wrote these usually religious texts, simply means ‘chapter’ while rs signifies ‘praises’; putting the two together produces babrs (i.e. papyrus), ‘a chapter of divine praises’. The reed from which the scrolls were made grows in only a handful of locations, principally along the banks of the Nile, making papyrus a key commodity for ancient Near East merchants. To make the link with ‘bibliomania’ we must sail north along the Levantine coast to the mighty Phoenician entrepôt of Gubal, whose principal asset was its proximity to the cedars of Lebanon, exchanged for papyrus from timberless Egypt. As literacy took off in the first millennium BC Gubal suddenly found itself at the hub of a booming paperchase, reflected in the city’s Greek name, Byblos - a Hellenization of papyrus (or babrs). The information-age equivalent would be renaming Los Angeles ‘Tinsel Town’ or replacing ‘Santa Clara’ with ‘Silicon’ for the valley outside San Francisco with an exceptional density of millionaires. So closely did Gubal (or Byblos) become linked with its chief import that it even gave the Greeks their word for ‘book’, biblâon (plural biblâa), from which we derive bible and bibliomaniac. Another closely related Greek word, papuros, passed down via Rome and the Battle of Hastings to become the English word for paper. And while we’re on the subject, ‘book’ derives from the writing-tablets made of beech (bôk in Old Saxon) on which runes were notched, while ‘library’ comes from the Latin application of ink to the inner bark or liber. Egyptian paper, Greek bibles, Latin libraries and Anglo-Saxon books - each bears lively witness to the many layers in our eclectic tongue.

Plato’s Timaeus (quoted above) has recently been enjoying a fresh lease of life as the original source for the Atlantis legend. The Egyptian put-down forms part of a lengthy preamble which leads to a description of the fabled continent just before it sank beneath the ocean waves around 10,000 BC. Atlanteans over the past decade have been joining ranks with a new breed of maverick Egyptologist, the latter bringing geological and astronomical data to bear in a controversial redating of ancient Egyptian civilization. One of the trailblazers is John Anthony West, former Manhattan copywriter turned astrologer, whose Serpent in the Sky (1979) popularised the ideas of Schwaller de Lubicz, author of an unorthodox study about the Great Temple of Luxor. But hang on a minute: where does Ibiza fit into all this? It just so happens that West’s second book, Osborne’s Army (1966) was a novel and like Norman Lewis’s Tenth Year of the Ship 1962, (see weekly article published Saturday 3rd August 2002) is set in a thinly disguised Ibiza.

Our subject was born into a comfortable New York family in 1932, making him a fully-signed-up member of the beat generation. After studying economics at Lehigh University, he worked as a copywriter in New York until 1957 (when his first short story was published), before giving up the rat race to join countless other New York beats on the road. Quo vadis? his fellow-admen might have asked. For many it was a toss-up between Paris and Ibiza and thanks to a private income West could have taken his pick; but in 1954 Hemingway had won the Nobel Prize and three of his most successful novels were set in Spain. Even though that country now lay under the iron grip of its dictator, the Pityusan archipelago remained, paradoxically, a unique and sun-soaked haven of freedom and tolerance. For a new generation of writers there was no real contest: Ibiza, in West’s own words, was ‘a beautiful, completely unsoiled place, the home of what was a very bohemian colony …’ Over the following nine years he became a key figure on the local scene, mingling with Dutch scribblers and working away on satirical short stories about the American way of life for journals like Atlantic Monthly and Shock. Ten were brought together for his first book, Call Out the Malicia (1961) translated into Dutch the same year (Huilen met de wolven). Throughout the early sixties he typed up his one and only novel, Osborne’s Army (1966) which enjoyed enough success to appear three years later in Dutch (Osborne’s rebellen) and in paperback as part of the Penguin New Writers series. In a biographical note West declares that it was conceived on a trip to Puerto Rico and written over six years on Ibiza. The island on which it is set is called ‘Escondite’ (Hideaway), but although West places it in the Caribbean, there can hardly be any doubt that the original is far closer to Ibiza:

The sierra forming [the island’s] spine ends in a cape of rock, a jutting tawny wedge three hundred feet high; stone bastions, cliff-coloured, terrace the top, and above these bastions, rising from patchwork greenery, stands the fortress … White, faded pink, faded ochre, mullioned with green, the town tumbles down the hollow of a hill; its apex, a ruined cathedral: its base, mansions graced the broad beach …‘You mean no one knows about this place?’Grimes spins the wheel neatly, corrects, and noses the boat up to a tilting jetty: ‘Sorta looks that way.’

Osborne’s Army,pp. 10-11

As we saw in Lewis’s The Tenth Year of the Ship, the character and name of Grimes, a well-known local painter, was simply irresistible for novelists. The gallery of island bohemians - most of them European - clearly points to a Mediterranean backdrop:

Awaiting the mail boat became ritual on Escondite … everyone gathered at Theodore’s bar long before the possible hour of arrival and drank away the interim - most of the natives showed up as well, so newcomers were greeted with a great deal of noise and waving. Even Marsh dropped work (perhaps this boat would bring that one right woman who spoke his language, not that it mattered). Stefan Verduin showed up, with Jan van Gent and Marja. Van Gent was considered Holland’s finest young poet: anthologies beginning at 1300 finished at van Gent. He had been writing advertising copy and television plays.

p. 128

The duo is probably Jan van Gent and Marja are Hugo Claus and his wife Elly. Other Ibiza legends either appear under their own names (Grimes and Stephen Seley) or with appropriate aliases: the primitive painter Charlie Orloff thus becomes ‘Freddy Rosoff’ while Ernesto Ehrenfeld, failed writer and successful art dealer is transformed into ‘Kurt Krummer’.

Expatriate life on Hideaway features a certain amount of bitchy infighting but is relatively idyllic until the beats find themselves jostling for elbowroom with two new waves of visitors. The first to come ashore are the hippies -

soiled jeans and filthy shirts - unbuttoned but tied pirate-fashion at the east - many were draped with bead necklaces; all wore sandals or bare feet; their beards ranged in texture and scope from the lichenous to the dendroid; each had a rucksack strapped to his back; a copse of guitar stems bristled. The women were similarly dressed and equipped, and coiffed like octopi … They didn’t do very much; they just hung around, a scruffy, idle, self-styled hagiocracy. Sometimes they went swimming, sometimes someone strummed a guitar; occasionally there was a lethargic verbal exchange in the cult’s unintelligible Bêche-de-Mer, but mostly they just sat in the shade, in big disorderly groups, smoking the free marijuana and staring at their feet, or at nothing at all: occasionally one would stand, signal his chick, and they would slouch off together … There were not enough habitable houses remaining to shelter all these newly arrived painters and writers; some set up tents on the beach.

p. 188-90

Even less welcome are the grockles (a dated word meaning ‘holidaymaker’), whose arrival on a massive scale threatens the status quo in a far more sinister way:

The town was ‘quaint’, the natives ‘friendly’, the art colony ‘picturesque’, the beach ‘sandy’. Though he pointed out the impossibility of docking the big cruise ships and the need for a landing launch … And Simon Sr. chuckled as his son concluded; ‘So you see, Dad, the place is wide open and waiting; an absolutely golden opportunity and nobody has any sense there.

p. 206

'Nobody has any sense there.' The Simon dynasty would be delighted by developments on the docking front: Ibiza will soon have a dique large and sophisticated enough to berth the Starship Enterprise itself. Cruise-ship tourists come in all shapes and sizes: ‘nouveau-rich garment czars, branch chiefs, henpecked chiropodists, rasping viragos from fashion magazines, Kodachrome families and Iowa schoolteachers with peeling arms.’ But this colourful cross-section of western humanity proves too much for our eponymous hero, who gathers around him an unlikely taskforce of ten likeminded heroes, bent on expelling the unwanted visitors and turning back the clock as far as it will go. First taking a party of grockles hostage, they manage to secure the immediate departure of not only the entire tourist community, but also shopkeepers, hotel personnel, parking-lot attendants, travel agents, gigolos and even balloon vendors. A concession is made for construction workers, now needed to restore the island to its original virgin state, a rather daunting task: how long, the author asks rhetorically,

would it be though before the destruction workers could blow up, tear down, carry away, and dispose of the hotels and apartment houses, the cabarets, cinemas and equipment sheds? … Before the latanier palm and ceiba tree again grew on the site of the Waffle-orama and the U-Needa-Hotdog? Before the fraternal and benevolent sea silted over with sand the debris-filled harbor, and coral again grew, and fish swam in their rightful dominion?

p. 281-283

The Pityusan branch of Friends of the Earth might well ask the same question, substituting fig-grove (figueretes) and underwater Posidonia meadows for latanier palm and ceiba tree - and Pizza Hut and Macdonalds for the gastronomic concessions. The following morning a line of destroyers blockades the bay backed up by troop transports. The rebellion is soon over, the instigators apprehended, and the free world breathes an immense sight of relief. The last thirty pages of the book are given over to screaming headlines in a variety of typefaces and languages. The final extended piece is heavy with unconscious irony: Progress can resume its stately march now that the oddball lunatics have been removed from the picture.

By the time Osborne’s Army was published West had left Ibiza of his own free will and was busy mugging up astrology and Egyptology in London. His new career as guru of alternative prehistory began modestly with The Case for Astrology (1970), co-written with his Dutch translator Jan Gerhard Toonder. This was followed by the unexpected global bestseller Serpent in the Sky: the High Wisdom of Ancient Egypt (1979) and a companion volume, The Traveller’s Guide to Ancient Egypt (1985). These would have joined the ranks of countless other alternative Egyptology books, barely noticed within dusty academic departments, had West not in 1989 approached a geologist from Boston University, Professor Robert Schoch, to establish a scientific base for Schwaller’s observation that the Sphinx had been eroded by water. As it is, his work has led to something of a prehistoric tidal wave. Those wishing to know more about this controversial redating of the Giza complex might like to consult the author’s webpage at http://www.jawest.com

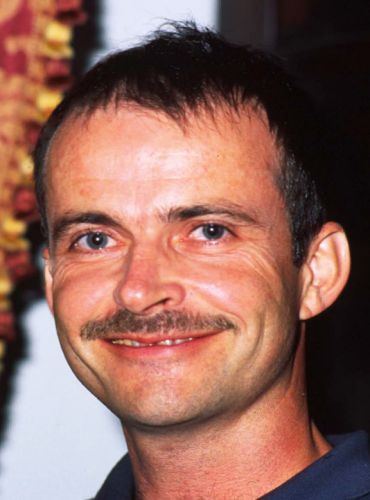

The former advertising copywriter, satirical scribbler and astrologer is not just a rebel Egyptologist though: he also takes guided tours of grockles round the monuments of ancient Egypt. It tickles the heart to know that the author of Osborne’s Army now ministers to the very package tourists earlier at the receiving end of his biting satire. A gentler, more peaceful character (rather Hollywood in sola topi) gazes out from his webpage, one that recently wrote the Foreword to a children’s book, The Story of Bes (2000) which is all about the principal deity of Ibiza. Back in a fortnight’s time with more on that tale - the recovery of a lost papyrus …

Martin Davies

martindavies@ibizahistoryculture.com