For an archipelago of such modest dimensions, the Pityuses certainly have their fair share of archaeological secrets - real or imaginary. In weekly article published Saturday 26th October 2002, we saw that Bes’s sanctuary could well be lying concealed beneath the weeds of Dalt Vila, while in weekly article published Saturday 9th November 2002, we speculated that James (or even Jude) stopped off on an evangelising mission to Iberia. For the sake of argument, let us imagine he did exactly that. What on earth would his boat have looked like? This week we are going to answer that very question, starting with the subject of book-titles.

Would you - be honest - ever take a serious look at a novel called Pansy? The authoress herself must have had doubts as she eventually chose Gone With the Wind instead. Another author - a prickly character - scrawled the German equivalent of Four-and-a-Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice on his title-page. He subsequently pruned this down to Mein Kampf. Trimalchio in West Egg is our third non-starter: its creator was convinced that this was the only possible label for his literary masterpiece; fortunately his editors disagreed and sent it to the printers as The Great Gatsby. Which brings us to our current book: how could you know that Ted Falcon-Barker’s Roman Galley Beneath the Sea (1964) had anything to do with Ibiza? Cyprus, you might think, or Sardinia. Cyrene or Syracuse at a pinch. But Ibiza? Your Chief Bibliomaniac himself would never have taken a second look at this little gem if the blonde diver who appears three times on its jacket hadn’t let him in on the secret. She can be seen first rummaging about on the seabed, then elegantly conveying an amphora to the surface and finally wearing a low-cut number up on deck. She is one of Ibiza’s living legends and her name is Bel Barker.

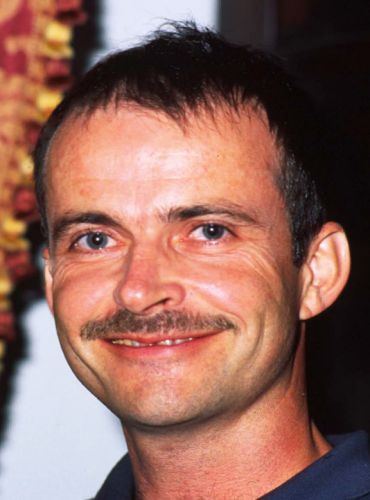

Bel must be one of the most attractive women ever to have set foot on this glamorous rock. You may have seen her on the front cover of the Pacha magazine a few years back, but she is far more than just a cover girl for fashionable glossies. Back in the sixties an old weaver taught her the secrets of her craft and as a result Bel became the only person on the island capable of making the thick woollen worsted, once a staple of the local dress. She has passed her professional secrets on to a few others so that the ancient tradition is no longer in danger of disappearing and deserves a special feature (take note, Ed.), but I would like today to focus on her first husband, Captain Ted, pioneer and author of six books on underwater archaeology.

The Falcon-Barker c.v. would sweep the board in any Boy’s Own Olympics. Brought up in the south of France to a Cuban mother and a father who prospected for diamonds in the Belgian Congo, he ran away to Australia from an English public school aged fourteen, volunteered for the army the following year, was directed into the Intelligence Corps and found himself as a spy in Damascus before parachuting behind Japanese lines into New Guinea. After the War he became a photographer, learned to fly, bought a publicity business, infiltrated the Communist Party as an undercover agent and finally started diving shortly after acquiring a yacht. For relaxation he strode off to the Bulgarian Alps to photograph the world’s last remaining Thracians. One of his many unusual traits was a natural immunity to venomous snakes. Which brings us to Ibiza, where he had his first big break in the underwater treasure business:

One day I was in a small café having drinks with some Dutch friends when the subject of sunken treasure and lost cities came up. Hans van Praag, a geologist from Java who had settled in Ibiza after the takeover by the Indonesians, and who now ran the local art gallery, mentioned that years before while on holiday in Yugoslavia he had seen walls beneath the water of a bay near Dubrovnik. The fishermen there had told him a fabulous tale of a sunken city once known as Epidauros, settled by Greek colonists from the original Epidauros in Sparta. Approaching archaeological authorities for more information, he was surprised to be told that it was all an old wives’ tale, nothing in reality existing beneath the waters at all, since the Greek city had been destroyed by barbaric tribes driving South from Germany.The Reluctant Adventurer(1962), p. 196

Needless to say, the authorities got it all wrong. In 1958 Ted, Hans and Bel mounted a full-scale expedition which established once and for all that Epidauros was there beneath the turquoise waters of the bay, an adventure written up in 1600 Years Under the Sea (1960), Cap’n Ted’s first book. The following two diving seasons (June-September) were spent prospecting the Maghreb coastline for ancient wrecks but the returns were generally meagre. Back on Vara de Rey in the winter of 1961-2 they started casting about for their next stunt. Ibiza had no sunken cities, but there were plenty of half-submerged rocks and treacherous shoals. The shallow strait between Sa Conillera and Illa des Bosc was an obvious place to look for ancient luxury items:

The reef stretched from Conejera Island to an outcrop of the mainland. As shallow as 6 feet in parts, it was what we had thought: an almost invisible danger to anyone of greater draught trying for a short cut across to the port [of San Antonio, then Portus Magnus]. As we had deduced, any ship caught in a south-westerly gale would have been hard put to round Conejera Point. As a last resort it would have tried the passage and ripping its bottom out on the sharp rocks, would have sunk in the sheltered waters sloping gently down to 120 feet.Roman Galley Beneath the Sea (1964), p. 39

Good thinking, Watson. They decided to canvas northern diving clubs and get some professional divers to help them in their quest. Cap’n Ted continues:

The first two weeks’ diving showed that we were on the right track, and that our deductions had been correct. Amphorae of all kinds, mostly in broken condition, dating from 400 BC to about AD 200, were scattered in an area of about one square mile. But we were not there to collect pieces of amphorae. What we wanted was a complete ship.Roman Galley Beneath the Sea, p. 44

They began to focus on an area where the amphorae pieces were all consistent with a type from southern Spain of about AD 50. And who was it who eventually found the complete vessel. Dr Who, of course! While playing with a baby octopus, the English actor Jon Pertwee discovered that its rocky home was in fact a buried amphora, which turned out to be stacked next to dozens of others. The wreck had been lying there all along, hidden by a protective blanket of fine sand and weed. Over the following weeks they carried out a painstaking excavation, first establishing the size of the wreck, laying a grid of numbered 10-foot squares, photographing each one as the sand was removed by a suction hose and keeping an exact visual record in layers of every stage of the excavation.

The finds included several hundred amphorae (one of which, completely sealed, was drunk on Hans van Praag’s birthday), brushwood to protect the pottery from impact with the hull, bronze and ceramic oil lamps by the thousand, Roman copies of black-and-red Greek vases, jars containing caulking bitumen and purple dye and large numbers of coins, chiefly from the reign of Nero. The star pieces were jewellery, one-of-a-kind vases, figurines and terracotta heads. Among the jugs and pots were numerous types from every part of the Mediterranean never before encountered - one even resembling a modern teapot. 1964 estimates for a unique small silver pouring vase stood at $60,000. You can add a nought for its present-day value. Then there was a dancing faun, an exact replica of a piece excavated in Pompei, also worth a king’s ransom. A complete set of weaving and pottery-making tools provided evidence of artisans on board. One particularly intriguing find beneath the ship’s keel was a bronze bowl with a fish design, obviously from China. The author concludes that it must been part an earlier wreck and have travelled via an overland route as sea trade between Rome and the Far East only got underway during the reign of Hadrian (AD 117-38), two or three generations after the latest coin found on the site of the wreck.

This book is special for several reasons. Firstly, not only is the text totally riveting but it is laced with just the right amount of dry Aussie humour. I thus learnt more about diving after half an hour in my armchair than during the course of a lifetime’s swimming. Then there is David Adcock’s first-class design, whereby photographs, drawings, diagrams, maps and plans complement the text perfectly: as well as photographs of all the principles players and every type of object brought up from the deep, there are diagrams and drawings of all the vital things an armchair diver should know before strapping on his aqualung, from the workings of the ear and barracudas to how to measure out an ancient wreck. Finally in a fascinating Epilogue, Falcon-Barker gives free rein to his extremely lively imagination: we can see the 500-ton vessel setting out early one June morning around AD 50 from Ostia, laden with oil lamps (several thousand of which were deposited off Conillera) plus a cargo of mixed goods from all over the Empire: glass from Tyre, oil from Spain, timber and venison from Gaul, pottery from Germany, marble from Tuscany and Greece - ‘the list is endless’. Three weeks later it arrived in Alexandria, gateway not just to Africa but to India and the whole of the Far East. Ivory, precious metals, cotton, papyrus, bitumen, ebony all poured through the city on their way north and west. As the Greek metropolis par excellence it also held a special fascination for Roman art collectors, and Falcon-Barker explains why he thinks the wreck had been specially commissioned, very probably by Nero himself, to bring back as many varied works of art as could be obtained on a voyage round the Mediterranean. He quotes Petronius to bring the point home:

The world entire was in the hands of the victorious Romans. They possessed the earth and the seas and the double field of stars and were not satisfied. Their keels, weighed down with heavy cargos, ploughed furrows in the waves. If there was afar some hidden gulf, some unknown continent which dared to export gold, it was an enemy and the fates prepared murderous wars for the conquest of the new treasures … The simple soldiers caressed the bronzes of Corinth. Here the Numidians, there the Seres wove for the Romans new fleeces and for him the Arab tribes plundered their steppes.Petronius, the Satyricon (quoted in Roman Galley Beneath the Sea, p. 112)

Were there any Christians on board when they left Egypt heading west? Nero had not yet begun his systematic persecution of the new religion which was beginning to undermine his sovereignty. Let us continue our fantasy a little longer. They stopped off at Apollonia (in present-day Libya), Carthage and finally Cartagena on the Spanish Levant before heading for Marseille where they hoped to lay up for the winter. It was late September when a sudden gale blew up as they approached the cape just south of Denia. They steered a course for the safe harbour of Portus Magnus, took a short cut between the two little Pityusan offshore islands and there came to grief. We can imagine the better swimmers making it to the shore, perhaps one of them using a sealed jar with early Christian texts as a lifebuoy. Well, why not? He or she would have been one of the very first to bring the new faith to the Pityuses.

So with Nero’s (or Judas’s) treasure-boat we have come to the end of our archaeological exploration for the time being. In a fortnight’s time, something completely different.

Martin Davies

martindavies@ibizahistoryculture.com